*This is a guest post by a friend of mine who is brilliant and thoughtful and compassionate and patient and, well, all-around fabulous.

*Guest Post by DYMPHNA

This blog post is a brainstorm I had after reading several posts (‘here‘ and ‘here‘) on this blog regarding the idea of communication, particular why spoken language, which seems so natural for some, is more difficult for others. First, I must own the fact that I have a pretty strong relative privilege in this vein. Spoken language comes naturally to me, so I am writing all of this with the caveat that I might be totally wrong. If Autistics who are less inclined to spoken language correct me on anything I write in this blog post, listen to them, not me. Secondly, this is an analogy and all analogies are imperfect; my hope is that this might provide an accurate framework through which people who grasp spoken language easily might be able to understand the difficulties of those for whom it does not come so easily. (This process for learning music is way out of order from how people actually learn music. Please don’t kill me, music educators.)

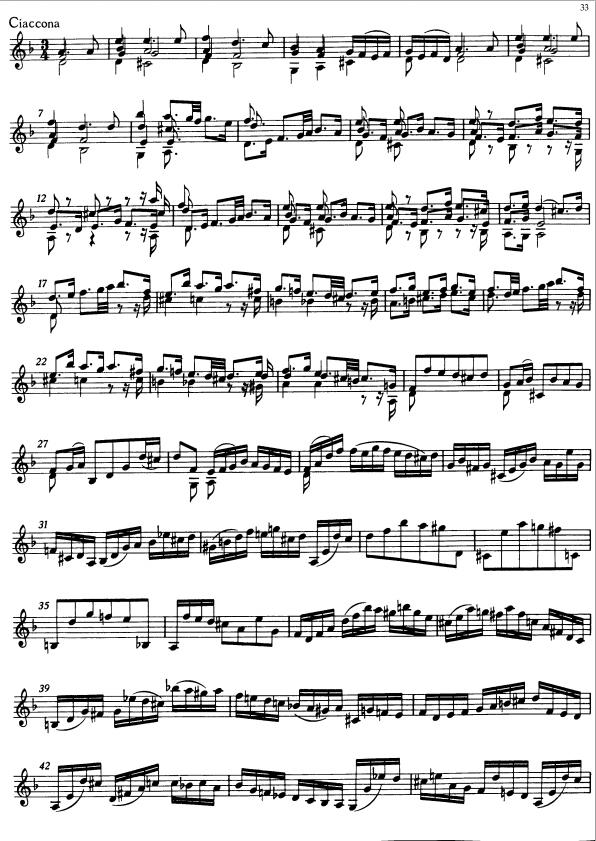

Okay, so, in this analogy, you are going to take this page of information and realize it into meaningful sound:

[Image description: Picture is the first page of the Chaconne

from Bach’s Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004.]

Now, for many of you who haven’t learned anything about musical notation, you are already at a loss. The picture above is literally meaningless to you. There are some horizontal lines and there are dot’s connected to vertical lines and there are these weird symbols that look like a lowercase b and a #. If you haven’t learned to read musical notation, the only things on this page that you even recognize are some arabic numerals that you have no idea how to interpret and this Italian word at the top “Ciaconna”, which the dictionary defines as, “a slow, stately dance of the 18th century or the music for it,” a definition which is not particularly helpful. With the resources available to you, you have established that this is an Italian dance from the 1700s. So in order to realize the page I put above you, you need to become fluent in musical notation and have the ear training necessary to understand what the pitches are and how to keep time properly, a process which many people find quite difficult.

So, having learned all you need to know about musical notation, you’re ready to perform the Chaconne, right? Well, probably not, as you have no idea how to play the violin. (Violinists, you are playing the piece on the piano. If you are also a pianist, you’re playing it on the flute. If you’re also a flautist, you are playing it on the musical saw. If you also play the musical saw, you need to just accept the premise of this analogy and move on.) If you are not a violinist, and I imagine that most of you are not, you don’t even know how to set up, hold, or tune the instrument, let alone produce a decent sound and then connect those sounds into a meaningful piece of music. So now that you understand what the notation means, you need to tackle the actual physical reality of learning how to play the instrument, a skill that takes years to do competently, decades to do proficiently, and half a lifetime to do masterfully. You need to learn how to hold the instrument and the bow and all sorts of skills about how to make the correct sounds come out of the instrument. Likewise, before you can do any of that, you have to learn to set up and tune the instrument, skills which are quite challenging to the beginning player. (As someone who has attempted to play the violin on several occasions, I can attest to this.) The process usually involves tedious work on many minute elements of technique that are by themselves very difficult, such as using different bow strokes, crossing strings, and pressing the fingerboard in the correct location. Moreover, you have to keep track of all of these elements of technique while attempting to accurately realize a score of music, so in addition to the difficulty of playing the music, you are simultaneously applying the skills you’ve learned in step one.

Congratulations! Having done that, you have the skills needed to accurately realize the first page of Bach’s Chaconne, a skill that will land you zero audiences and communicate very little. What most people don’t realize is that very little information is actually given to the musician by the composer. Many elements, such as the subtle ebb and flow of time, the varying loudness of any given instant of music, vibrato, etc., the elements that make music expressive and, if you’ll pardon the expression, musical, are not given to the performer by the composer. If the performer performs the work exactly as written on the page, it will sound mechanical and banal. This is why proficient musicians spend a great deal of their time focusing on interpretation. They are trying not only to reproduce the pitches and rhythms indicated on the page, but also subtlety that music needs to be truly compelling and persuasive.

All right, having done all of that, you can now convincingly convey great musical ideas. Musical ideas written by Johann Sebastian Bach. While you certainly bring something of yourself to the table, none of these are ideas that you originally had. The basis for all of these ideas was written almost three centuries ago. In speaking, this is analogous to someone being able to convincing recite a work by Shakespeare. A great skill in its own right, but all the while we’ve still fallen short of our actual goal, which is to communicate our own ideas effectively to others. Right now we are only equipped to communicate other people’s ideas, albeit with our own twist.

I would like to pause here and draw some of the analogies between playing the violin and speaking. First of all, there is the process of developing a rudimentary understanding of what music is, which corresponds to having a crude and basic understanding of the English language. I will discuss the full understanding in just a moment. Next, we have to negotiate the physical reality of playing the instrument. We might have a fantastic conception of what the Bach Chaconne should sound like, but that means nothing if we lack the ability to realize it on the instrument, which is an inherently physical process. This, not surprisingly, corresponds to the actual motor process of forming words. For many of us, those processes seem pretty simple, but imagine what it would be like if they didn’t come naturally to you. Imagine if everyone seemed to have this innate aptitude for holding the violin and producing pleasant sounds on it while you are struggling to get notes out. Most people, having able or neurotypical privilege, take this ability for granted, so I want you to imagine a world where, instead of speaking, we communicated by playing the violin, a skill for which many people do not have the natural aptitude. This is where the Social Model of Disability comes into play. For those who find speech easy but playing the violin difficult, this world is fine for them while they would be disabled in the violin world. Likewise, those who find playing the violin easy and speech difficult are disabled in this world but fine in the violin world.

Resuming our violin analogy, there is a lot more to speech than playing the Chaconne by J.S. Bach. As I stated before, most people seek not to reproduce the ideas of others, but rather to convey their own ideas, which they do in real-time. In music, this equates to improvising, a skill that isn’t necessarily that difficult provided you don’t seek to convey anything that complex. However, there are still things to consider. First, you want to have the semantics of what you are improvising accurately reflect what you are trying to convey. I cannot think of an accurate analogy for this, so please leave an idea in comments if you have one. On top of that, you have the elements of music theory, which is essentially the grammar of music. Certain notes in certain contexts convey specific meanings that might not be conveyed in another context. Without using this correct syntax, what you are trying to convey will start to sound random and disorganized or possibly just “wrong”. This process comes very easily to most people, but understanding grammar is no simple task, a fact which anyone who has tried to learn a foreign language can testify. In our native language, we can just say what “sounds right” without having to put too much thought into it. In the same way, a native tonal musician might be able to tell you that a C-Sharp and a G need to resolve to D and F intuitively without explaining the theoretical reason behind this in the same way that you know whether to use “me” or “I” in a sentence. However, just because this process comes to us intuitively doesn’t mean it isn’t going on and it’s something we oughtn’t take for granted when thinking about communication.

So what is the point in all of this? I’ve drawn all of these parallels about how spoken language is like playing the violin. The point in all of this is the following:

First, the process that we think of as intuitive and easy is not necessarily that easy or intuitive for others. I don’t find playing the piano very difficult, but most people would struggle to play something rudimentary on the piano because they are dealing with all of the things I mentioned above. Moreover, at the piano, you at least have the reassurance that if you press a key, a musically sounding sound will come out, something that isn’t guaranteed on a violin or when speaking (which is why I chose the violin for this analogy).

Second, I want people who find things to be easy and intuitive to think about what it might be like for those who don’t find the process so intuitive. As many people are not instrumental musicians, I challenge you to think about what challenges you would face in the world if, instead of communicating via mouth sounds in natural language, we communicated by instrumental music. Hopefully this exercise will expand your empathic process so that you can understand what it means to be disabled without medicalizing us or assuming we have a deficit.

Third, I want everyone to think about some of the strategies you might employ in this alternative violin world where you are struggling with many of the rudimentary elements of communication. Maybe, since you don’t want to have to deal with the challenge of writing a syntactically correct and semantically accurate statement while dealing with the difficulty of playing the instrument, you might instead use an existing melody that approximates what you want to say instead of attempting to improvise something of your own. Maybe in this violin world, you’ll get special education for doing this, seeing that you have musical echolalia and your ability to use spoken natural language, a skill that frustrates you as you want to use it to express yourself while no one uses that skill, is seen as a “splinter skill”, not inherently useful, but rather a means to develop your violin skills, which are the “correct” way to communicate.

I think this exercise in empathy is much more effective than the wholly appropriative and mocking “Be Disabled for an Hour” idea that many people try out. Of course, you need to recognize that this will not give you a perfect view into our world. Being that you don’t live in this culture in which you are disabled, there are things that might not occur to you that are realities that disabled folks have to deal with every day. Thus is the nature of privilege. But I hope this has expanded your notion about how disabilities impact your life and how society defines what is and is not a disability.