Yesterday I wrote a post, Your Child’s Been Diagnosed. Now What? There are so many things to add. But something I wondered often during those early years was – what good is a diagnosis if the “interventions” the professionals suggest and say will help, do not? Now this is not everyone’s story, but it is ours. All the recommended “interventions” did little, if anything, to actually help her. In fact, I would argue that some of the interventions we agreed to, actually harmed her self-esteem. And the general rhetoric, disguised as factual information, surrounding autism, encouraged her to feel damaged and at fault for the suffering of others. No child should feel they are the cause of other’s pain and suffering. And yet, so many do.

Once we began looking for schools that might be a good fit, we were even more horrified. The choices were not – which one is best? – but became – which one will not harm her? This shouldn’t be a parent’s guiding question when looking at schools, but for us, it was. Will the staff be kind to her? Will they be patient? Questions like – will she learn? Will she be taught science, math, english, social studies? Those questions quickly gave way to – will she be harmed? Are cameras monitoring what goes on in the classrooms and hallways? Do they use isolation rooms? Do they allow teachers to use restraints? The best case scenario became less about education and more about physical safety and finding a place that did not harm or try to force compliance.

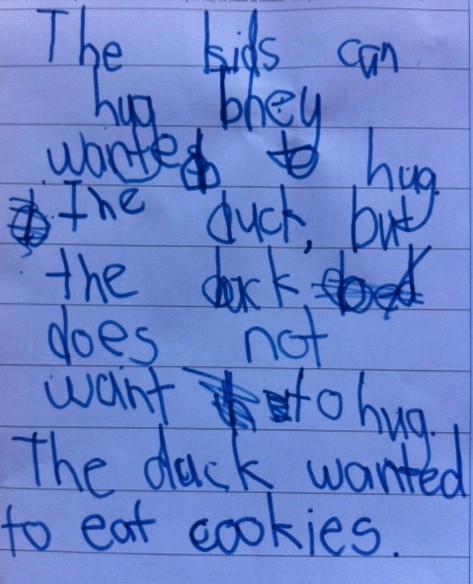

Academics were stripped down as it was “shown” that she could not understand basic concepts. Because she could not read aloud, she was given picture books. Because she could not answer the questions asked, the questions were simplified and simplified more and more and more until it was concluded she didn’t understand. Because it was determined she could not understand a simple story about a boy and his dog going on a trip to visit his Grandmother, she was given less “complex” stories. She was given “sight” words that were repeated for months and months, even years. Billy Goat’s Gruff became the center piece for a curriculum that continued for three years, despite our disbelief and protests. “Oh but we examine all the various characters in the story,” we were assured. “THREE YEARS??” we responded. “For three years?” “Yes,” we were told with pitying looks and the hubris and bravado I’ve come to recognize from those who are convinced they “know” and understand “autism” and therefore my daughter.

Some of the worst offenders are those who have dedicated their lives to autism. Those who are so sure they know, and as a result are no longer curious or interested in learning more. Those are the people who are asked to give presentations at Autism Conferences, they are the ones who write books, that parents, not knowing any better, buy. They are the ones we listen to and slowly as their voices are the loudest and most plentiful, we begin to doubt our instincts, we begin to soften our protests, we begin, slowly, slowly over time, to believe them. Our ideas about our child are whittled away. Our instincts are pushed aside to allow for those who know better, who have been doing this for “twenty years,” who have worked with “this population” and who, from having spent decades among children just like mine, know things I cannot possibly grasp or understand. (This, by no means, describes everyone, but it does accurately describe a great many, and sadly, often those who were in a position with the most power.)

We parents are told to see our children for what they are: Intellectually impaired, socially inept, incapable, lacking and unable to understand the most basic concepts. My child, as a result was shuttled off to learn how to tie her shoe laces and wash her face and hands. While life skills are certainly important they should not take the place of academics. So many of us are consoled with the idea that at least our child will be able to dress themselves, or not… in which case we envy those parents who have children who can. Our focus turns from philosophy, an exchange of ideas, history, english, poetry, literature, science, social studies, math and geography, to making sure our child can brush their teeth. Until one is accomplished, it is thought, the other cannot be introduced. A child who cannot dress themselves, surely cannot be introduced to Kant or Socrates or a poem by Yeats.

“Hey Emma, I’m curious, how is it that you know about WWII and Nazi Germany?”

“I hear you, Nic, and Daddy discussing,” Emma wrote over the weekend.

“Do you think it was right for Harry Truman to drop the bomb on Hiroshima?” my son asked.

“I have to learn more to say one way or the other,” Emma responded.

“Do you want to hear some arguments for and against the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima?” N. asked.

“Yes, I can better understand using the bomb if you tell me more,” Emma wrote.

There is so much more to say…