I asked Emma for her permission to talk about language retrieval issues, and specifically to describe some of what occurred during her first session with Soma last week. She said it was okay for me to do so. I’m incredibly grateful to my daughter for being so generous with what is personal information. She has given me her permission, but to leave it at that, would be wrong. To not acknowledge what this means would be negligent at best. She is unbelievably generous to allow me to share these things. I do not know how many of us would be willing for another to share such personal things about ourselves, and the trust she has bestowed upon me, the trust that I will not betray her… it is something I not only take very seriously, but need to acknowledge. To say I am grateful does not come close to describing the feelings of appreciation and awe my daughter inspires. If all human beings could take a page from Emma, both in her cheerful generosity in giving of herself so that others might benefit and her compassion and willingness to see the best in people, even when so many have said and done cruel things to her, this world would be a far better place for all of us.

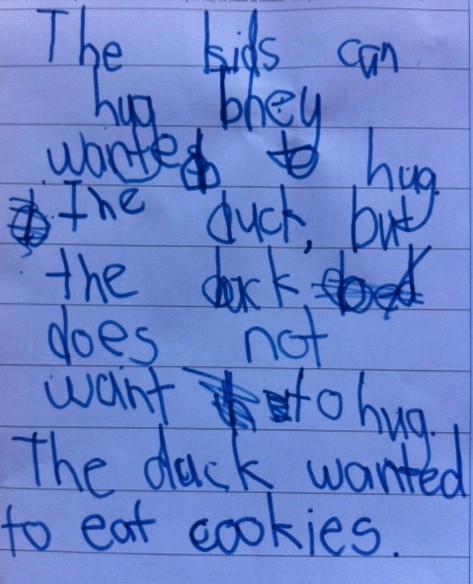

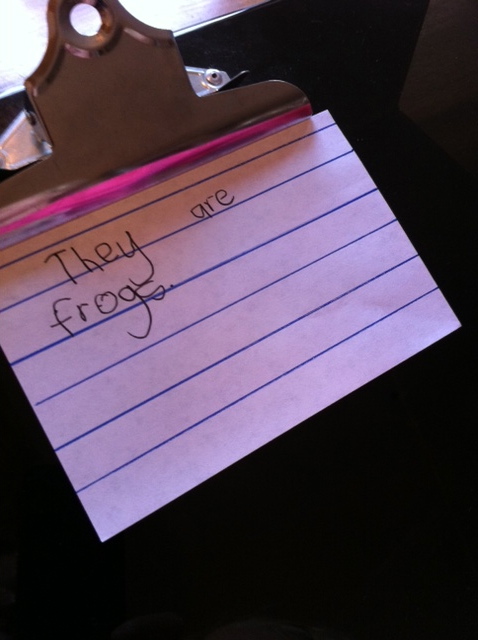

I wrote about Emma’s first session with Soma ‘here‘. What I didn’t write about was how after Emma pointed to a letter she was encouraged to say the name of the letter, just as her Proloquo2Go program does on her iPad. She was able to do so without hesitation. But when Soma put the stencil board down and asked Emma to say the next letter of the word she was writing, without pointing to it first, Emma would, more often than not, say a random letter. Soma then picked up the stencil board and again without hesitation, Emma pointed to the correct letter and was able to identify it correctly out loud. After Emma wrote a sentence she was invited to read the sentence aloud, but could not do so. This is a sentence she’d just written, one letter at a time. A sentence she’d created, yet was not able to read. It is not then surprising that Emma is unable to read a random story out loud, even though she is perfectly capable of reading it silently to herself and fully comprehending it. See related post about reading aloud, ‘here‘.

To see this broken down, to witness this at the level of single letter retrieval and not a whole word even, made it all even clearer to me. Which isn’t to say that Emma will never be able to do this. Perhaps at another point, perhaps once she is proficient in writing her thoughts and identifying a letter after pointing to it, one letter at a time, she will then be able to work slowly, patiently and without the anxiety of feeling expectations are being placed on her, perhaps then she will be able to come up with the next letter before she points to it and from there the next word and on it goes until verbal language can catch up to her written. But for now, it is imperative that every single person who comes into contact with my daughter understand how detrimental it is for her to have these expectations placed on her and then to have the inevitable conclusions drawn about her comprehension and ability.

My daughter is nothing short of brilliant. I am not saying this as a biased mother who is basing her thoughts on nothing more than some sort of convoluted tip of the hat to genetics, or a round about way of bolstering my own ego and intellect. I am saying this because I have seen the evidence. Since her diagnosis, Emma has been treated as though she were intellectually impaired when, in fact, she is intellectually gifted. This is, I’m sorry to say, something I am hearing from others. We have a growing population of children and people who are treated as though they are incapable, when in countless cases the opposite is true. The onus is on us to change our current teaching methods and the therapies we are employing and to open our minds to the idea that we have gone about this all wrong. This is what must change.