What would you do if the whimper in your heart could not find the right words to speak? What if you couldn’t control the things you felt compelled to say, even if you knew those who heard you would not understand? Speaking is not an accurate reflection of my intelligence. Typing is a better method for me to convey my thinking, but it is laborious and exhausting. So what is to be done with someone like me? Is it better to put students like myself, of which there are many, in a segregated school or classroom, is inclusion the better option or is there another answer? I was believed not capable enough to attend a regular school, nor was I able to prove this assumption wrong. In an ideal world these questions would not need to be asked because a diagnosis of autism would not lead to branding a person as less than or inferior. Those who cannot speak or who have limited speech would not immediately be labeled “intellectually disabled” and “low functioning”. We would live in a society that would embrace diversity and welcome all people, regardless of race, culture, religion, neurology or disability. Our education system mirrors our society and in both, we come up short.

In New York City kids like me are not attending mainstream schools because we are believed to be unable to learn complex subject matter. I was sent to both public and private special education schools, specifically created for speaking and non-speaking autistic students and those believed to have emotional issues. Because I cannot voice my thoughts and so rely on favorite scripts, my spoken language causes people to assume my thinking is simple, I am unable to pay attention and cannot comprehend most of what is said to me. As a result, none of these schools presumed that I, or the other students, were competent and their curricula reflected this. At the private school I attended for six years, I was regularly asked to do simple equations such as 3 + 2 = ? When I said “two”, because that was the last number spoken and my mouth would not form the word “five”, my teachers believed I could not do basic math. It was the same with reading and something as simple as being asked to define the word “cup”. I clearly know what a cup is, but when I could not say it, I was marked as not knowing. This school used the same fairy tale, “Three Billy Goats Gruff”, for three years as the foundation of a “curriculum”. At another school, this time public, while my older brother was learning about World War II and writing essays on whether the United States should have dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, my class was planting seeds in soil and asked what kinds of things were needed for the seed to take root and grow. When my classmates, many of whom could not speak at all, and I could not answer with the words “sunlight” and “water”, it was assumed we did not know the answers or understand the question. At another public school I spent months going over how many seconds are in a minute, minutes in an hour, hours in a day, but when I could not demonstrate that I understood either in writing or spoken language, it was believed I had no concept of time.

There is no test that allows me to show the creative ways in which I learn. I cannot sit quietly unless I am able to twirl my string, softly murmur to myself and have a timer nearby. I cannot read aloud or answer most questions verbally, but I can type. My mind is lightning fast. I can hear a song and then replay it note for note with my voice. I have an incredibly large capacity to listen, learn and feel. I listen to conversations around me regularly and often wish that some parents would appreciate their children more. The other day on the subway a Mom said, “Shut up, you’re being stupid!” to her son. The boy was silent and put his head down. The Mom proceeded to play a game on her phone. I have learned that everyone is delicate. In that moment my body felt tremendous sadness. I see patterns in unrelated things, such as I am able to notice every article of clothing that someone wears on a given day. People’s attitudes are reflected in their choice of clothing. When the same clothes are worn over and over, I have the feeling the wearer is stuck. People’s self-confidence increases when wearing new clothing. My expansive vocabulary is impressive. I’ve listened to how people put words together my entire life. As I have made sense of the words used, I have been able to understand their meaning, though I am unable to ask for definitions. I notice people’s sadness, even when they are smiling. I almost feel like I am violating someone because I can see inside of them and know their feelings. I’m told I use the written word in unusual and interesting ways. I have been published in magazines and blogs. I give presentations around the country on autism and gave the keynote address at an autism conference this past fall. I am co-directing a documentary, Unspoken, about my life and being autistic and I hope, one day, to be a performer.

The best education I’ve received to date in a school is at a private non special education school, where none of the teachers or administration has been given “training” in autism or what that supposedly means. They do not believe I cannot do things the other students are able to do. In fact, though I am just fourteen-years old and technically should be in eighth grade, I am doing upper level work. I am treated respectfully by teachers and students alike. My typing is slow, but the class waits for me and gives me a chance to express myself. During a recent Socratic seminar where the students were expected to speak on the book we had just finished, everyone waited for me to type my thoughts and gave me time to have my thoughts on an earlier point, read later. In my theater class the teacher began the semester with non-speaking work. We learned about mime, silent theater and the importance and impact of physicality while performing. I have been asked for what I need in order to excel, and accommodations have been made, I know, but I hope and believe that I am not the only one benefitting from my presence at such a terrific school.

There is a saying in the disabilities community, “Nothing about us, without us.” A complete rethinking about autism and autistic neurology is needed if special education schools or any schools are going to educate those of us who think differently. Believing in the potential of all students is not on any test. Presuming that each and every student, whether they can speak or not, can and will eventually learn given the necessary supports and encouragement is not commonly believed, but it should be. Wouldn’t it be great if autistic people’s ideas were included in designing curriculum and the tests that are meant to evaluate them. Isn’t that what you would want if you were like me?

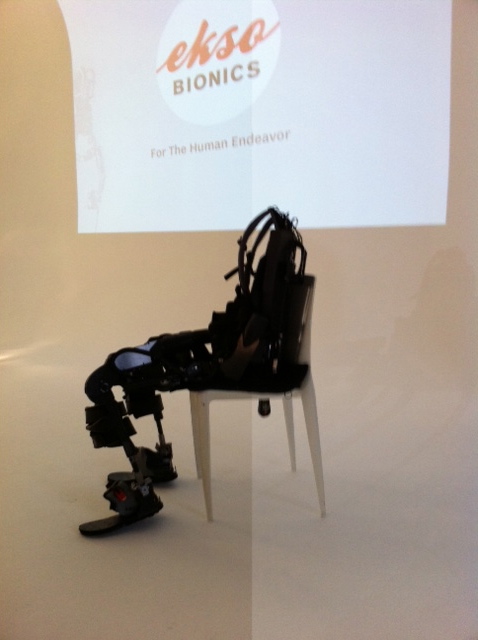

Photograph: Pete Thompson Photo