On autism.com‘s web site, they write:

“What is the Outlook? Age at intervention has a direct impact on outcome–typically, the earlier a child is treated, the better the prognosis will be. In recent years there has been a marked increase in the percentage of children who can attend school in a typical classroom and live semi-independently in community settings. However, the majority of autistic persons remain impaired in their ability to communicate and socialize.”

After receiving an autism diagnosis for one’s child, most people go to the internet to learn more. Quotes like this one abound. What these sites do not say, cannot say, is what will specifically help your child – What interventions, if any, will make a difference, what biomedical, dietary & behavioral approaches will work?

This quote is also from autism.com’s website:

“Conclusion Autism is a very complex disorder; and the needs of these individuals vary greatly. After 50 years of research, traditional and contemporary approaches are enabling us to understand and treat these individuals. It is also important to mention that parents and professionals are beginning to realize that the symptoms of autism are treatable–there are many interventions that can make a significant difference.

The logo for the national parent support group, the Autism Society of America, is a picture of a child embedded in a puzzle. Most of the pieces of the puzzle are on the table, but we are still trying to figure out how they fit together. We must also keep in mind that these pieces may fit several different puzzles.”

A parent of a child with autism quickly finds they will need to read enormous amounts, speak with a great many “specialists”, sift through the endless opinions (often stated as fact), and try to make sense of all the various articles, papers, news items and books currently in print on autism. In addition they may watch the numerous documentaries, interviews, YouTube clips and all the other visual forms that exist relating to autism. Having done all of that a parent must make decisions as to what they can and cannot do, what they can and cannot afford to do in their attempts to help their child. While they are making these decisions, they must cope with their own emotions, trying hard to keep depression, worry, panic, fear, sadness and guilt at bay. They must learn to manage these feelings while continuing to research and do what they are able to with the hope something they try might just help their child.

But most important perhaps, we must never give up. We must try in our darkest hour to see the light. We must treasure our child’s differences, celebrate our child’s uniqueness, rejoice in our child’s strengths.

Years ago Richard and I went to a couple’s therapist. He listened to us both individually and then asked us to meet with him together. As we sat side by side on his couch he told us he didn’t want to hear about our latest disagreement, he was much more interested in hearing from each of us what the other had done right in the last 24 hours. We were told to go home and keep a journal, recording all the things the other had done that was kind, thoughtful and helpful. He encouraged us to examine each act, to consider things we perhaps took for granted. It was the single most helpful advice anyone ever gave us.

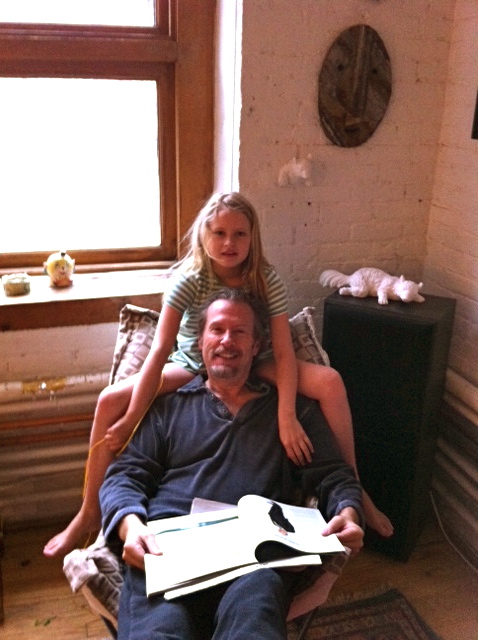

This blog is a version of that exercise. While I do my best to accurately document Emma’s progress or lack of, while continuing to try different interventions, I also try my best to celebrate her. Let me concentrate on her strengths while I continue to do everything in my power to help her build on those same strengths and perhaps she’ll discover new ones.

For more on Emma’s journey through a childhood of autism, go to: www.Emma’sHopeBook.com