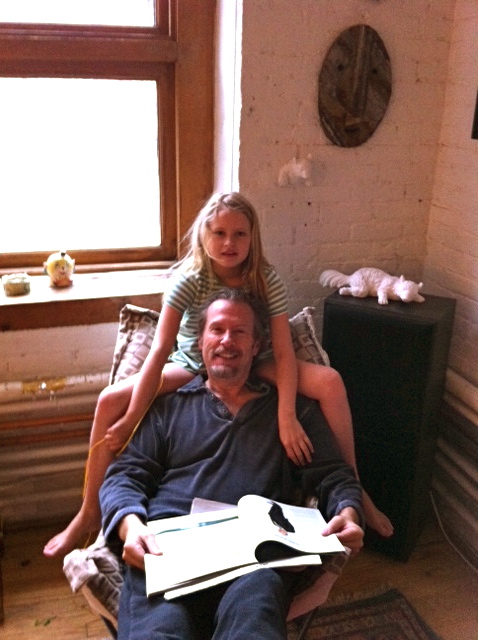

Emma on the 4-wheeler

Perhaps more exciting than even the ARC (Aspen Recreational Center) is the 4-wheeler kept up on the ranch. For those who are not familiar with this piece of machinery, it is a cross between a kind of Hummer version of a motorcycle and an open air golf cart. My two nephews, Colter and Bridger, are cringing at this crude and citified description of mine, because it is actually an essential piece of powerful ranch equipment used to change sprinkler heads, and to haul a variety of other things. Things I do not pretend to know about. To me, it is the vehicle we use to go looking for coyote, fox and other wild life up on the ranch. Last summer we found a den of coyote pups, so cute(!) whose mom lay basking on a nearby rock, unruffled by our intrusion, she didn’t move a muscle as we rode by within ten feet of her pups. (I know Colter and Bridger – you guys might want to just shut your computer down at this point – it’s got to be painful to read this description.)

Now that I have thoroughly humiliated my fabulous nephews with my utter ignorance in all things to do with ranching, I will attempt to move on. When Emma arrived in Aspen the night before last, one of the first things out of her mouth was – “Go on the 4-wheeler?” Followed by, “Go to DuBrul’s (my cousins’s) house?”

When we told her she couldn’t do either of those things, she then went for her back up list. “Go see motorcycle bubbles?” (This requires interpretation as this is what Emma calls the 4th of July fireworks, which we missed this year as we were in New York.

“No not going to see motorcycle bubbles. Go swimming in indoor pool. Yeah, go to the ARC.”

When we informed her that as it was almost 9:00PM, this wouldn’t be possible, but promised to take her the following day, she said, “Go to outdoor pool?” (Meaning the Snowmass rec center’s outdoor saline water pool)

Finally tired of our feeble excuses about the late hour and how everything was closed, she conceded sadly, “Time for bed.”

But the following morning the list was proffered up and there wasn’t much we could say as our excuses of it’s too late, no longer held any weight and she knew it. So off to the ARC Emma went and then a trip to the grocery store where she was able to procure her favorite chocolate milk from Horizon, before getting the 4-wheeler from the barn. We were also able to load a bale of hay into the front to carry back to the house to set up with a bull’s eye so that Nic can practice his archery skills.

Bringing hay back to the house for Nic

It’s good to be home with the family!

For more on our escapades and Emma’s journey through a childhood of autism, go to: www.EmmasHopeBook.com