You’ve described yourself as a “nonspeaking (at times) Autistic.

“Yes, I think the phrase “nonspeaking at times” captures my experience, and also that of others who do have speech capabilities but can’t always access them. Because one can speak at times does not mean that speech is a reliable form of communication for that person. Also, when someone can speak some of the time, others may not notice that they are having trouble speaking. I have sometimes not been able to speak and other people just thought I was “being quiet” or did not have anything to say; that dates back to childhood.”

Why did you make a video of you not speaking?

“I made the video because we need to change some of the ideas about “high functioning” and “low functioning” Autistics. Not being able to speak is equated with “low functioning”. A constellation of characteristics are said to be true of only “LF” people, such as self-injurious behavior, toileting difficulties, and not being able to speak or having limited speech, while “HF” people are said to have another set of characteristics, also fairly stereotypical, such as being “geniuses” who are good at computer programming and lack empathy. These binary divisions don’t address the wide variety and range of characteristics of Autistic people, and paint a limited picture of individual Autistics, many of whom defy (not necessarily on purpose!) the expectations surrounding their “end” of the autism spectrum. I have always known I can’t speak on a regular basis, but the conversations about “nonverbal” people assume that I have a different experience when in fact it’s not so different at all.”

Can you talk about how and why you sometimes are unable to speak?

“I can’t say I speak “most of the time,” since most of my waking hours are not spent talking. I showed on my video, even when I am alone, I frequently can’t talk. I don’t need to talk at those times, but I am very aware that if I were suddenly presented with a situation in which I needed to talk, I would not be able to. I am, however, usually able to make what some Autistics have called “speech sounds,” which means that I can say something, even if it is not exactly what wanted to say. I have a number of reasons for not being able to speak at any given time. I distinguish between not being able to talk at all and having trouble with word finding, which does not make me lose speech, but can have some interesting results when I find a word that is not the right one! I can go “in and out of speech” several times during the course of a day.

The following list has some of my reasons for not being able to talk. These are not in any particular order: Sensory overload, being tired, reading or seeing something disturbing, thinking more in visual images than in words, trying to talk when other people are talking too fast and not taking turns‒which is not limited to the autism spectrum, although a lot of literature exists about teaching us to take turns. Some of that teaching is necessary, but I think it should be introduced to non-autistics as well!”

Are there other things that stop you from being able to talk?

Another thing that will stop me from being able to talk is to have big chunks of time where I am not talking because I am mostly alone, like when my son spends the weekend with his dad. After a weekend spent primarily not talking, I am not used to it and have trouble getting started again. It does not take more than half a day of not talking before I need to urge myself to take it up again. It’s the inertia of not doing it, plus I have to remind myself, consciously, of how to move my muscles (mouth, lips, larynx) and intentionally will myself to speak, which does not always work. Sometimes my son will ask me “Mommy, are you having a hard time talking?” and if I manage to say “Yes,” I am able to start talking again, although I can have a hard time formulating sentences and finding words for a bit.”

Of all the items on the list, which ones affect you the most?

“The thing that will stop me cold, suddenly switching from being able to speak to not being able to utter a word is seeing, reading, or hearing something that is disturbing. I write indexes for nonfiction books. Some of them have very graphic descriptions of things like genocide or war. I did my “make myself talk experiment” on a day when I was using voice recognition software to do data entry for a book that had ten chapters of very disturbing material. I used VRS a lot at that time to save my wrists and fingers for playing the organ. Since I am a visual thinker, not only was I reading it, but also seeing it in my mind, like an awful movie that I did not want to watch,. I found myself typing instead of dictating, and realized I had been doing so for maybe half an hour. I said to myself, “Why did I switch to typing?! I don’t want to be typing!” and my experiment was underway. I spent the next two hours trying to make myself talk, with no success. I was online at the time, so was typing to people telling them about the experiment. Some of them were a bit concerned that I was trying to force myself to talk when I couldn’t, but I needed to find out if I would be able to talk if I tried really hard. My answer was provided after two hours, in the form of a small squeak. That’s the only sound I could make after all that trying. I had two realizations as I finally ended my experiment, still not able to talk except for that squeak. The first was that it reminded me of when I had an epidural for a procedure and tried (yet another!) experiment to see if I could wiggle my toe. The doctor got “mad” at me and told me I was actually wasting physical energy I would need to recover from the procedure. I had the same feeling of exhaustion from trying to make myself speak. The other thing I realized is that maybe I should be carrying an autism card with me in case I was at the scene of something upsetting, like an accident or crime, and could not talk to first responders. Some things that I find disturbing and thus making me not able to talk are not that dramatic. It can be someone saying something that I did not expect them to say (not limited to “bad” things) or anything unexpected or surprising.”

What are your earliest experiences of not being able to speak?

“When I was a child, there were many times when I could not speak. I think very early on, I was not very aware that I could not talk at times; I simply did not talk when I couldn’t. I definitely spent a lot of time looking at things like dust motes in the air and the thread on my blanket and other tiny little interesting things; I have no idea if anyone tried to talk to me and got a response, how fast a response they got, and whether or not I was conscious that I wanted to say something but couldn’t. In later childhood I was more aware that I was both not speaking and wishing I was. I attributed loss of speech to being “shy,” and was angry at myself for being that way. I spent quite a few decades having times of not being able to speak, including the entire day once, and being angry at myself for not being more “brave.” Reasons include some social ones, such as being afraid of another person for whatever reason, feeling “on the spot,” having a particularly anxious day, people interrupting me. I think people were not aware they were interrupting me, as my speech was so tentative. Other reasons include being tired, having more visual thinking and not the accompanying language-based thinking, since my thinking is visual with an audio soundtrack and the soundtrack sometimes drops out for whatever reason. Sometimes the lighting or the color green will render me speechless. I love green! It is very mesmerizing! It often makes me unable or disinterested in speaking, especially the green of a large field of grass. Eeeeeeee!!!!!”

When did your views regarding your inability to speak at times change?

“After I learned about autism, I started thinking more about the reasons I lost speech. I met people who either could not talk at all, could not always reliably access speech (like me!), stuttered (like me, again), had trouble finding words, or had to say other words, circling around until the right one was selected, such as one of the “big words” I used to get teased about in school.

One of my ongoing word-choice problems is “French toast.” Early in the morning, I can’t think of “French toast,” for some reason. I ask my son if he wants “Um, um, um, um, …. uh… (then I draw a square shape in the air, since I can see the French toast clearly in my mind) … um, square things!…. French toast!” Since my son now knows that “square things” means French toast, sometimes we just stop at “square things” and he says yes or he will say, “Mommy, I want square things!” and we laugh and I make the French toast.”

Does it trouble your son that you can’t talk at times, or have trouble saying what you mean?

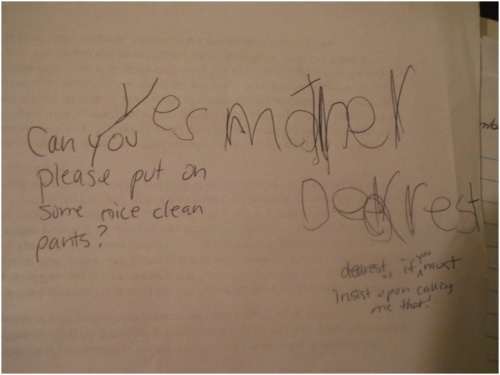

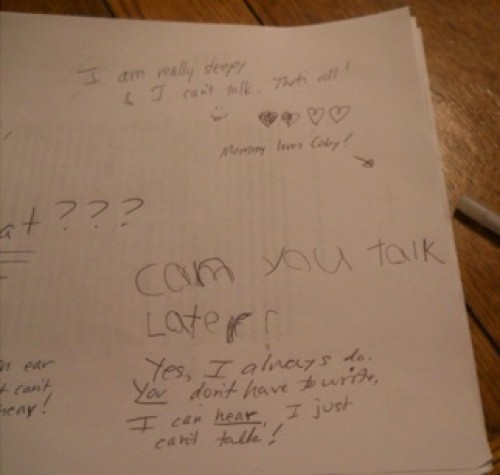

“My son is very good at talking about things he doesn’t like, but I don’t assume that he would feel entirely comfortable directly telling me things he doesn’t like about me. The things he does say indicate support rather than discomfort. A few times I have been annoyed at myself for stuttering and he says “Mommy! Don’t ever be mad at yourself for stuttering!” or, a few times, “Mommy. Stuttering. It’s a way of life.” I don’t not-communicate with him, so he does not feel ignored. I use alternative ways of communicating with him, just not talking. I write, point, use some of my extremely limited repertoire of ASL signs. I once was writing to him about what to wear to church and he wrote back “Yes, mother dearest!” He (as is true of most people I write to) matches my communication mode and writes back. I have written to him (and to others) “You don’t have to write to me; I can hear you!” He has noticed, and told me, that when he comes back from visiting his dad I “seem different.” We have talked about his coming back as a transition point- the house is suddenly noisier, and definitely “talkier.” I have often said that my child talks to think, so we are quite different in that way. I am working on what would make the transition from “kid gone” to “kid in the house” an easier one for both of us.”

For people who do not have difficulty speaking, they may have trouble understanding how someone might be able to speak in one situation and then not able to in another. Can you talk more about this?

“Some abilities are not there every single time a person wants to access them. This is true for all people, but for an Autistic person, these fluctuations in abilities and access to abilities might be more pronounced. If I don’t play the organ almost every day, it’s almost like I forget how to play it. That’s why I always practice on Saturday night and Sunday morning before church. There is no way I can go in there cold and play like I want to. Think of something like delivering a presentation. For most typical people, there will be good days and bad days, presentations you wish you could do over, and days when you were really “on your game.” Or, think of your favorite sports team and player. Some games are not so good; other games the team really does well. But playing the organ or hitting a home run is not an essential life skill (ballplayers and organists feel free to disagree!). But when it comes to anything considered really basic, like being able to talk, a sense of mystery surrounds the topic, when a person can do it one time and not another. I maintain that it’s not that different anything else, but is more noticeable and pronounced when it’s something that is expected of everyone, and when one can do that “expected thing” most of the time. Maybe for some of us talking is an extreme sport, in the sense of having to really work, practice, try hard, take risks, and think consciously about what we are doing, whereas for some people the ability to talk is very natural and not even a conscious effort.”

Talk about the idea of language and thinking.

“I have read more than one author who opines that without language there is no thought. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Language includes both written and spoken words, as well as picture-based communication systems like PECS. Not talking (and also not writing) does not equate with “not being able to think,” “being lost in an unknown world” or anything other than specifically not being able to talk. For some people it could mean a lack of focus on “the present moment” (how many people are fully present in each moment anyway?!) or not being able to think in words, which is another one of my reasons for not talking. But it is not, generally speaking, accurate to assume that because someone can’t talk, they can’t think. You wouldn’t look at someone who has a tracheostomy tube and go “Oh wow. That person can’t think!”

What is it like when you’re unable to speak while in public and are expected to?

“It’s a bit nerve-wracking, but only in situations where people do not know me well and are expecting that I can speak like a non-autistic person. I try to anticipate what I will need to be able to communicate at those times but I can’t always build in my own supports. When I am with friends, it’s no big deal if I can’t talk or can’t talk much. In work situations it’s more difficult for me to feel calm about it. Unfortunately this expectation is not limited to people who don’t know much about disabilities, so that I have had to really struggle at autism-related events where there really aren’t accommodations for Autistic ways of communicating. It’s an ongoing process for nondisabled people to learn about communication differences and to anticipate them so that Autistics and other people with communication disabilities aren’t doing most or all of the work to create our own accommodations.”

How do people react to you?

Really, I mostly don’t get reactions, because often the times that I can’t speak coincide with the other person continuing to talk, maybe because they think I don’t have anything to say, or that they are like “Well, if she’s not going to talk, I will!” I do get all kinds of reactions, from total acceptance to “you could if you wanted to- try harder” kind of thing that made me feel sad when I was making the video. Sometimes people don’t believe me when I say (in speech or writing!) that I have trouble talking. I have to be very clear that I mean not being able to talk at all. I have learned that “trouble talking” might mean not saying the right thing, or stage fright, and “I can’t talk right now” can mean “I am too busy to deal with you” rather than that I literally an unable to speak with words coming out of my mouth! I have had a few mixups when people did not know I meant “I can’t talk right now” very literally. Sometimes people just don’t quite believe me and think I am making it up. I am not sure why they would think I would go to that much trouble! There are also people who have never heard me stutter, who think that I don’t, even though I tell them I do. They are going to get treated to another video in a few weeks! I was finally able to capture myself stuttering at a time when I also had the webcam with me.”

Are there things that help you speak after a period of not speaking?

“I mostly just have to wait. I don’t particularly want to talk a lot, but I need to. It’s just one of those things that is expected, and it is expected that if I can do it some of the time, I can do it all of the time. It might seem that someone who can speak but loses speech at times would want to find ways to prevent speech loss, but I often welcome not being able to talk. It gives me a break from the exhausting task of speech production. My idea of the perfect conversation and this is ideal for a number of my Autistic friends, too, is two laptops or mobile devices or text-based equipment, but we can be in the same room together writing to one another. I don’t get a lot of this because I live in a rural area and most of the people I write to are long-distance. Some friends locally are very accepting but we don’t have any alternative setup other than me scribbling on paper. I also get way overloaded by hearing other people talk, as it challenges my auditory processing abilities and I can only take so much talking. If other people, whether or not they can speak, would type to me, I think I could get a lot more accomplished with the interaction with that person. Or, at least I think I could. If writing is not that person’s strongest form of communication, it will be a limit for that person. We should not be expected to always accommodate “talkers” and not the other way around. But it does take extra effort on my part because people can’t tell just from looking at me that I am a person who sometimes can’t access speech.

Ideally, we could take turns using each person’s communication strengths and weaknesses, assuming we are able to do that much. Of course, sometimes it just won’t work.”

Paula and her son’s writing

To read Paula’s blog, go to Paula Durbin-Westby Autistic Blog

Related articles

Thank you SO much, Ariane, for posting this. And thank YOU SO MUCH, Paula, for sharing your story, and taking the time to make this video. My son is only 5 and is non-speaking as well and this post SPEAKS volumes about what he goes through, volumes that I have not been able to adequately speak myself in my attempts to inform family and friends. I am emailing a link to this article right now to everyone in our family, it will explain so much to them that I know they have been wanting to understand. THANK YOU. THANK YOU. THANK YOU.

Oh Katrina, thank you so much for writing this. I’m going to make sure Paula sees it. I’m sure she’ll be very happy. I know I am!

I AM happy to see it!!!! I do know people who did not speak until much later in life, ages 5 and on up to 12 or so. If he is not going to speak, or even if he is, or even if someone reading this has a family member who talks on and on… I would suggest trying to put as many alternatives in place as you can learn about so that he has a variety of ways to communicate, other than whatever he is doing now (including body language that only his family might understand). I am happy to write with anyone in your family who has questions, but I don’t always answer really fast… also, to anyone else who wrote comments here, I am going to answer them all, but have to take it a bit at a time.

One thing I never knew, until that past few years, is that alternatives to speech would be very useful to me. And then once I did know it, it took a number of years to allow myself to realize that, yes, I too need alternatives to talking, and more than just going online in my spare time and communicating with my friends. I thought of AAC as something that only people who have REAL (LOL!!!) communication difficulties should be “allowed” to use. I need AAC of some sort or other, whether cards I have made (will post pictures of some of those on my blog soon), or pencil and paper, or an iPad, etc. All those will be helpful to me at times. They might even be helpful to more “typical” people who don’t have disabilities but who could benefit from communication alternatives at times. One thing that is hard is getting other people to agree to use them with me. Some people are less than enthusiastic about reading my scribbling on a piece of paper or even using email instead of phone! It takes me being willing to be :”out there” about using alternatives, and some days I don’t have the energy to do it.

Hi Paula, thanks so much for sharing your thoughts, feelings and experiences so honestly and directly. Our daughter Emma struggles with speech. I often wonder how this affects her comprehension. Many people have told us that auditory processing can be as difficult as expressive language, though frankly, most of the adult autistics we have met (many so-called non-verbal) don’t seem to have any or much difficulty in that area. In reading your interview you tell your son that you can hear him, so he doesn’t need to write too, which leads me to believe that verbal comprehension isn’t difficult. Is this the case?

When we talk to Emma we are never sure if she understands everything or not, because she doesn’t answer and doesn’t have a great deal of skill yet with other communication alternatives (writing, typing) or show any interest in going to get a sheet of paper, or typing etc, to make herself understood. This is where I can often go down the dead end street of worry about “other” issues etc, since we never seem to meet or speak to adult autistics talking about verbal comprehension as an issue.I worry something “else” may be a problem.

Another thing I was really curious about was why it seems so easy for you to access the words you want to use for writing, when the same words elude you if you are trying to speak them. Can you describe that more? What does it feel like?

Thanks so much again for sharing yourself so generously with us:)

Richard, I have a LOT of trouble with auditory processing, as do quite a few of the Autistics I know. I always assume, actually, that Autistics I meet and talk with do have auditory processing difficulties. If they don’t, that’s great, but I try to keep that in mind when talking. My difficulty in speaking at all, when I lose speech, is not really with the words themselves, although word difficulties make me slower at times when I am speaking, or lead me to saying something that is not quite what I wanted to say and then the conversation goes on, and other people are talking and I don’t get a chance to go back and correct or add to what I want to say, which is very frustrating. The difficulty in not speaking at all is that I can’t connect the words in my head with the ability to say them. I could be sort of screaming them (!) in my head really loud, but they don’t come out of my mouth. I think it is a motor processing thing, and when I get overloaded I can’t connect up the brain and mouth muscles. Also, when I am overloaded (a term that overs a lot of territory!) I am more uncoordinated in general, tripping over things, dropping things, not being able to turn my cell phone around in my hand so that I can get to the keyboard, stuff like that. I am using my new Boogie Board this morning to write a blog entry about pragmatic speech, turn-taking, etc. It includes things like the Boogie Board “saying”: “It’s my turn now,” “I would like to add to what I said,” “Might I be permitted to say a word or two?” 😉 “STOP! (Please?)” (for those REALLY frustrating times, and mostly as an example of what COULD be said, but maybe should not!) and things like that, because conversations with non-Autistics go at a very fast pace. When I am with other Autistic people, I often just say “I wasn’t done!” or “Let me say something!” in a voice that I have always thought that non-Autistics will find insulting. With Autistics, though, usually the other person says “Oh, OK…” or “Yeah, sure,” or apologizes… or keeps talking, At least I tried! And the opposite can happen and I let them person take a turn if I was talking on and on and on about something. I do the talking monologue thing at times when I am speaking, like when my son asks me a simple question and I give him the entirety of U.S. history as an answer. Argh! 🙂 So, my speech-generating capabilities fluctuate wildly, from no speech (which I often see as a motor/emotional/energy thing) to WAY too much speech (Too Much Information) and everything in between. The non-speaking thing happens almost every day, or at least several times a week. The “knowledge fump” thing happens a lot less, and typically with people with whom I am very very comfortable and on good speaking/listening/communicating terms with. But… not always. This is so not rocket science. And, nothing I write should be construed to be THE answer for your child or family member, or yourself. I do hope that people can think about it and learn their own answers by reading/watching this as well as the writings and videos and talking of other people.

Um. Just noticed. “Knowledge fump” should be “knowledge dump.” I guess people figured that out.

This article is made of win. Awesome Paula and awesome Ariane. Everyone should read this and know the things in it.

Thank you Ibby!

Richard, I have to think a lot about what I am going to write. I write fluently, but first I translate visual images or “feelings” about a topic, then find words. So, I’m at the point where “I know the answer (or my answer) to that!!” but it won’t be in words until later. The great thing about writing is that it is asynchronous and I can take my time- even when that time might only be seconds or minutes. And, there’s this great feature called EDITING. 🙂 I will write back, though.

Oh good, you’ll come back to say more? Because now after reading Richard’s question, I had another too. Which is to describe the “feelings” to words and that whole process more. This is something Ibby ⬆ has talked to me about in trying to understand Emma better. Can you walk me through that experience with an example?

Maybe not “feelings” as in emotions, but “a feel” about something. A sense impression. I will write more later; this is a really bad time with a lot of sensory overloading things going on around me!

Wow, that was tough to watch. Paula, thank you for making it. Ariane, thank you for posting it.

It’s so tough sometimes to watch Risa struggle. She has never been verbal, nor can she write. To look in her eyes and see, and KNOW, that she wants to communicate so badly but just can’t….it’s something I’ve never been able to witness without being emotional. 😦 Nor something I think I’ll ever get used too.

((((Angie)))) (((((Risa)))))

I AM wishing you luck and want to know how it goes and if it helps. I am hoping it will!

Well, I was not intending to have what I wrote below as a reply to Angie. At any rate, I do want to say to Angie that it is more difficult to know what someone is thinking if they don’t use language-based communication (word-based such as speaking, writing, PECS pictures (those imply words and often have words written below the pictures). While I know what it is like to be frustrated that I can not use language temporarily, I don’t have an ongoing inability to use it. There are times when I can speak and also do not have any way of writing (don’t have materials or computer with me). At some point I can get back to it, though. I can’t say more since I don’t know your situation, other than what you wrote, but hoping that if Risa wants to use language-based communication she will find a way with your help.

Wow. This hits very close to home. I hate when I can’t talk. It doesn’t happen all that often and I’m good at covering for myself, but I hate it all the same.

Fabulously articulated! I have been working with children and adults on the Autism spectrum and their families since 1998. The best way I have found to try and get family members to understand how difficult talking can be for their child/sibling/etc is to say ‘it’s one of the hardest things to do; it’s like calculus for them’. With your permission, Paula, I would love to be able to share this, written here in your own words. You’ve definitely described it so much better!! Thank you for helping the rest of us understand. You made some very important points. And, I will be sure to watch my ‘turn taking’; thanks for making me aware of this. =)

Amy, you can definitely share it. That’s why I made it. You can also find my blog article, with some different comments, which says a lot of what I said here but maybe in a bit different ways.

For those who may not know Paula’s blog and I will add it at the bottom of the post as well, it is: http://paulacdurbinwestbyautisticblog.blogspot.com

It is also on my blog roll if you want to click to it directly.

Paula, I’m already a huge fan of your writing and advocacy work, great to see you here too! I have selective mutism and can really relate to some of the things you’re talking about here.

Thanks, Ariane, for showcasing these conversations!

It’s been an utterly selfish pursuit on my part. I am really grateful and honored that Paula was willing to share herself as she has. Thank you again Paula. Can’t really thank you enough! And thank you for reaching out with this comment! It makes me happy!!

Oh. This makes a lot of sense. Thank you for taking the time to put it into words for the always verbal amongst us. My son, who has an excellent vocabulary, is on the spectrum & often seems to ‘not bother’ to describe experiences. I have sort of understood why, but this post explains it far better. Thank you x

Jacqui, when I was younger I did not even think about putting experiences into words. As I have said, I was largely unaware of any differences when I was younger. Now that I am 53, and happened to have a day where everything was just right for making the video, I finally did it (have been thinking about it for probably a year!) And, I have a lot more video clips I made on the same day. I did not expect this one would get all the attention it has because I thought other people had probably done something similar. I have 5-6 more clips plus now am making another entry using my newly-acquired (since yesterday) Boogie Board. Maybe your son might decsribe things later in life, if he is even interested in doing so. I know a number of Autistics who have absolutely no interest in discussing autism, so who knows what might happen.

I am glad to read how someone else experiences this. I am relatively fluent most of the time but for me periods of extreme stress or sudden stress and then I can’t talk or can’t talk fluidly.

The question about comprehension wasn’t addressed to me but since everyone is different I will say that when I was still pre-speaking I did comprehend well for quite a long time before I spoke. However for me, when stress causes the ability to drop off depending how badly for the initial bit I can sometimes also not be sorting out what is said. That tends to pass fast and is sometimes intermittent, Almost as if it was a trip where at the furthest extreme edge they both go.

The hardest thing as an intermittent speaker is that the bulk of the people you deal with – even or maybe even especially professionals seem to think there is verbal and there is non-verbal and someone they regard as verbal not speaking is making a choice. (Although I do know some who have chosen to just give it up entirely because of it’s unreliability is itself a stressor, it is still not the kind of choice these people seem to mean)

I have had what is probably a record for mas as far as my speech being often halting and non-fluid and while on some level I accept this about myself on another I can’t help but observe myself and worry about how bad things must be that this goes on and on.

It’s easiest to cope with non-speech when you are in a situation where you don’t need it but for me it doesn’t seem to happen those times. To need it desperately to prevent some strange conclusion being made about you and not to have it makes things kind of horrific. Earlier in the year before everything spun right out some counselor not long on listening skills would not listen to me when I begged her to just stop talking. She stressed me to the point where I couldn’t speak and I knew full well if I couldn’t with her the result would be quite literally the team of people in a van showing up to check on you because I had no way to articulate that would make things worse and wasn’t needed.

I’ve had to be more matter of fact about my autism this year because any illusion I had that I could pass at all (which apparently was largely illusion) couldn’t be maintained in the face of the ongoing issues with productive speech. I hate in a way that programs I have gone to for decades people are now overly sympathetic sigh and view me differently but that’s a different battle.

I wish the actual literature actually handled speech as more of an ongoing issue rather than a goal to achieve that gets confused with the larger communication issues.

“The hardest thing as an intermittent speaker is that the bulk of the people you deal with – even or maybe even especially professionals seem to think there is verbal and there is non-verbal and someone they regard as verbal not speaking is making a choice.”

So this is exactly what I once believed. I hate admitting this. But it is. I could not understand how it could be that a person has language and then suddenly doesn’t. My brain couldn’t wrap itself around this concept. This is the reason I so wanted Paula to talk to me more about this.

I have also had a similar thought about Em’s ability one day to read or write and then stumble over things I expected or assumed she “knew” then when she had trouble worried that she didn’t really “know” whatever it was. But this thinking is wrong I now see. It’s not about knowing and not knowing it’s about ability and the ability shifts and is not a constant.

Thanks, as always, Gareeth for sharing so much. I’m really grateful for your comments. Always. Always.

It’s because you do admit things you once thought and your journey from Ariane that your blog is so valuable I think for all.

Aww.. Gareeth… thank you. Thank you…

Gareeth, THANK YOU.

Pingback: A Conversation with Paula Durbin-Westby « Raising kids with diagnosed/undiagnosed autism

Thankyou for this. Writing from the UK, I have found the classifications of verbal and non-verbal very frustrating. My two autistic children would be classified as verbal but many people don’t realise their difficulties with speech. Both have periods when talking is too difficult for them and when they prefer to communicate through other methods such as miming, typing or drawing pictures. We follow their lead in the home but the challenges come from other people (including professionals) who don’t (or won’t) recognise their difficulties and continue to talk to them when they simply can’t cope. I hope other people read Paula’s interview because it brilliantly describes the difficulties that people like my children have with speech.

Hi Deb,

Thank you so much for reaching out and commenting!

Very beautiful. Thank you for sharing. Non speaking doesn’t mean “nobody’s home.” Language comes in many shapes & forms. To be silent, either by choice or by disability, should not diminish the person. The wonder of modern computers and iPads is that many silent Autistics now have a “voice,” and we are finding some very remarkable people who used to be thought as “unthinking.”

This was one of the things I was stunned by at the Autcom Conference. The sheer number of non-speaking people who were communicating often with poetic prose their thoughts and feelings. I’m so grateful to Paula for sharing about this, because I think it’s something (I know I haven’t completely understood) people don’t fully appreciate or get.

❤

To Paula and from Paula:

All through my life (and I am almost 84!) I have only known 2 Paulas well, so when I hear that someone’s name is Paula, I immediately gravitate toward them. And you, Paula, are so articulate and have so much wisdom, that I am happy to get to know all that you have been able to unlock and communicate with others, whether autistic or not. You are remarkable, and I can see-hear-understand the love that you share with your son. I watched your video, and I think it is the one thing above all else that makes me see into the incredible frustrations that sometimes non-verbal people have to deal with.

You said something about playing the organ. Could you explain more about that? My granddaughter (Ariane’s Em) has always been able to sing and remembers all the words and all the songs perfectly without being able to communicate those same words in speech. What do you think music has to do with being able to express oneself?

You are “dearest Mommy” to your son, but to me you are “dearest Paula”

Granma Paula

Hi Paula. I don’t think of myself as “unlocking” anything at all! I simply can speak at times and at other times am nonverbal. Re: playing the organ- I started playing the piano when I was 4. I learned to play the organ when I was in my 20s. I used to think I was “bad” at singing, so only did it when no one was around. Later on, I loved to sing, and feel perfectly happy getting up in front of a bunch of people and singing, even on short notice (assuming I know what the song is!) With a song, one can memorize the words, so there’s less of a problem coming up with words in the first place; that involves a lot more tasks. If I am being VERY nonspeaking, I will not be able to sing, either. At church, where I am organist and choir director, I sometimes have trouble getting started talking at rehearsals, but so far have not become completely speechless at a rehearsal. During the actual church service, I sometimes have problems saying the prayers, less problem singing along with the organ, can have trouble saying the spoken parts but can get up to sing a solo or with the choir. So, singing is probably easier in general.

P.S. Thank you for the kind comment. I sort of have that same attraction to people named Paula. We are very few! I have met more Paulas later in life, but when I was a child I was the only one and, of course, felt that I was “strange” for having that name. It could have been something else, though. 😉

Thank you, so much of this resonates with me! I find it particularly frustrating when my capacity to process other peoples speech escapes me as I can’t fill in gaps with non verbal language. I always endeavour as far as possible to confine important exchanges to text based communication, it is more reliable, safer and comfortable.

Yes, written conversation is the most reliable for me, too. I sometimes make recordings for my own personal use, but have found that if it’s more than a few sentences, I can’t really process the recording that well, so don’t use that technique very often.

Pingback: On Peter Singer, Anna Stubbenfeld, and Rape | Thing of Things

Pingback: Down the rabbit hole with WorryFree, as sung by the Crystal Gems | Metonymical

Pingback: “i’ll do anything once” | Metonymical

Pingback: And she was (speaking) | Metonymical

Thank you for this amazing conversation! It clearly describes the challenge of speaking! I am one of the Assistive Technology facilitators in our school district and I can’t wait to share your insight with parents and students that are early in their journey. One thing I worry about for our students is making sure that we are providing adequate reading and writing instruction so students will become literate. I want them to have writing/typing as an accessible alternative to speech for communication. We are spreading the word about AAC, like communication devices and iPads, but from this conversation, I think we need to expand our options to include paper and white boards for drawing too. Thank you again for sharing this!

Pingback: autism diagnosis: deciding on pathways | Metonymical

Pingback: Wherein I think too much (but not too too much) about (not) speaking | Metonymical